An interview with Walt Curnow, published in The Gurdian : https://www.theguardian.com/books/2017/feb/16/ahmed-naji-prison-made-me-believe-in-literature-more

After seeing a photo of him, Zadie Smith imagined Ahmed Naji as someone wild and antic. (“Rather handsome, slightly louche-looking, with a Burt Reynolds moustache, wearing a Nehru shirt in a dandyish print and the half smile of someone both amusing and easily amused” she observed in the New York Review of Books – without having met him.) Just a short extract of his prose allegedly gave one reader heart palpitations, and, for one judge, his language – “pussy, cock, licking, sucking”, according to court documents – was enough to justify a two-year jail sentence.

It’s hard to equate these intense, fleeting impressions with the quietly spoken man in front of me sipping green tea.

Naji is best known internationally for being imprisoned for the sexual content and drug references in his novel The Use of Life, in a society where these subjects remain largely taboo.

However, sitting in his apartment close to the Nile in central Cairo, Naji plays down the image he has acquired as a result of his plight, and the themes that got him into trouble.

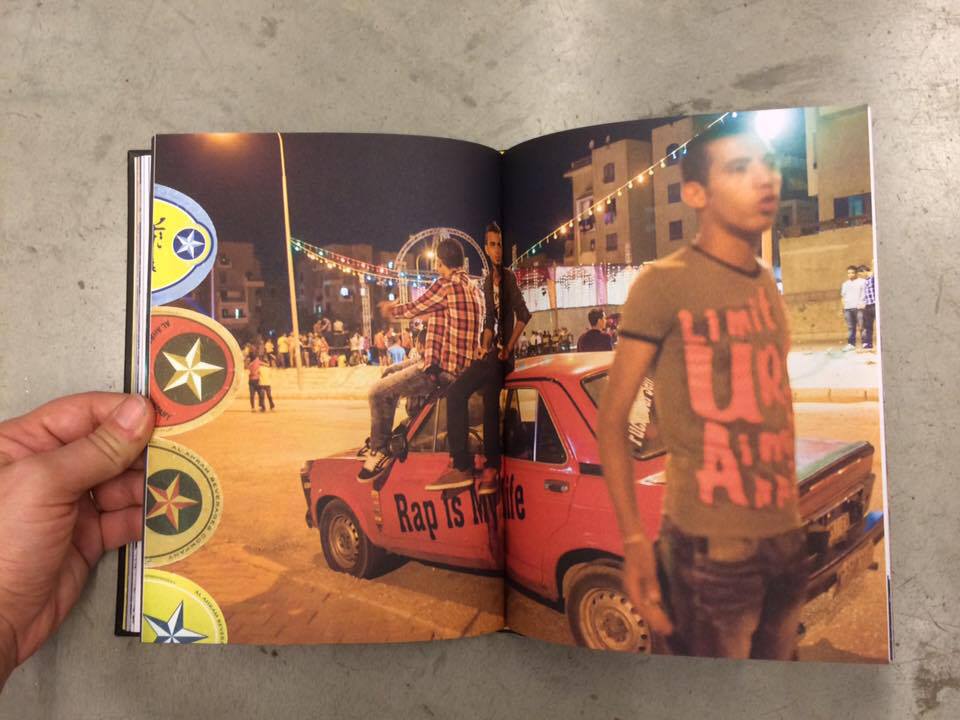

A blend of existentialist literature, fantasy and social criticism, The Use of Life follows Bassam, a young man who lives in an alternate Cairo, which Naji imagines as a grubby metropolis that has risen from a series of natural disasters that levelled the city. Filled with irreverent references to masturbation, fetishes and pornography, the book is consistently transgressive. Bassam’s opinions and ideas are also knowingly progressive – having sex with an older woman, keeping transgender friends, indulging in drugs and drink.

“Sex and drugs play a very important part in Cairo,” says Naji – while stressing that they are not the main themes of his novel. As he sees it, The Use of Life is about “the history of the city and how it has been designed … and how people in this Kafkaesque maze are trying to find a small piece of joy”.

The 31-year-old author first ran into legal trouble in 2015, when a chapter of The Use of Life was published in the state-run literary magazine Akhbar al-Adab. A male complainant, who said the passage came to his attention only when his wife ridiculed him for allowing such material into their house, alleged that reading Naji’s descriptions of sex and hashish-smoking gave him “heart palpitations, sickness and a drop in blood pressure”.

In January 2016, Naji was acquitted by an Egyptian court. But a month later, a higher court fined him £1,000 and sentenced him to two years in jail – the maximum sentence – for violating public morality, as enshrined in Egypt’s penal code. (The editor of Akhbar al-Adab was fined £430 for publishing the chapter.)

Naji’s lawyer, Mahmoud Othman, describes the chaotic legal process leading up to the sentencing as unprecedented.

“There was not enough discussion or attention paid to what we said in defence and the court refused to listen to a witness who is the head of Egypt’s general book institution,” he says. “They issued the verdict quickly, in less than an hour, without the announcement even being made in court – we found out the verdict from a security source.” Naji was the writer in Egypt to be jailed over a novel extract published in a newspaper.

Finally, after more than 300 days behind bars, Naji was released on appeal on 22 December. Now out, he is reluctant to say much about his time in jail, apart from revealing that it had affected his health and that one of his cellmates was the prominent revolutionary Alaa Abd El Fattah, with whom he discussed literature. “Jail is jail,” he says, quietly.

He does, however, take solace from being the latest in an international line of literary outlaws. “Joyce had something related to the same problem, because he’s using dirty words and it seems like it was a huge battle in the 1930s and 40s. And in the US, for example, when you read Kerouac and Ginsberg,” he says. “It’s about words that people are using in the street which suddenly have another meaning when people use them in literature. How can I know about all this and not use it in my writing?”

Naji is not the only Egyptian writer to go to jail, but he is the first to be imprisoned for reasons of morality. Others have been put behind bars for political or religious reasons, among them the novelist and short-story writer Sonallah Ibrahim, a member of the “60s generation” who was jailed between 1959 and 1964 during a crackdown on dissent by the nationalist president Gamal Abdel-Nasser.

Ibrahim was one of Naji’s most vocal domestic supporters, even appearing in court for his defence. He was one of more than 600 Egyptian and Arab writers, artists and authors to sign a statement calling for his release. As Naji’s case gained attention, his defenders were backed by international cultural figures including Woody Allen and Patti Smith as well as authors Dave Eggers, Philip Roth and Zadie Smith.

Naji seems unfazed by his new-found fame, but says he read an Arabic translation of Smith’s novel On Beauty in jail before he knew about her support for his release.

“It was a sign for me to believe in my literature more,” he says. “Before jail, I used to see myself mostly as a journalist and found it more difficult to be motivated. Now that is easier and has become a habit. I write fiction for two hours every day.”

This week, a leading Egyptian publisher took the risk of publishing a new collection of short stories by Naji. Mohamed Hashem, owner of Merit publishing house, is a patriarchal figure on Egypt’s literary scene and is no stranger to run-ins with the authorities.

He says that he decided to publish the stories because “I believe in the freedom of expression, freedom of thought and belief, as well as freedom of literary creativity. There shouldn’t be any kinds of restraints on the mind.”

He points out that though Naji’s language might seem bold, it is no more transgressive than that of One Thousand and One Nights.

“If you open [that] or other books from the Arabic-Islamic heritage, you will find an explicit language magnified by thousands of times more than in The Use of Life. And those authors were not called heathens or judged by anyone,” Hashem says.

Naji, meanwhile, reveals that while in jail he secretly started writing another novel, now about a quarter complete. He won’t divulge what it’s about, but another book that he read in jail, passed on to him by his friend Abd El Fattah, might give a clue. “I’ve just discovered an amazing writer,” he says. “China Miéville.”

He is due to appear in court again in April and is aware that he could go back to jail. If he is acquitted, he says, he plans to move to either Washington DC or Hong Kong at the end of the year.

After everything, Naji downplays suggestions that his sentencing was for political reasons. “I don’t think so. Of course, I heard some conspiracies and a lot of rumours but we didn’t have any evidence to support it,” he says. Some members of parliament even attended his trial and tried to change the law – frustratingly, it was unsuccessful (“The Egyptian political scene is complicated,” Naji says).

“I’m not a writer with a message,” he insists. “I’m more of a writer with questions. I’m not what they call in Egypt an enlightened writer or thinker.”