In August 2014, an Egyptian citizen named Hani Saleh Tawfik came across issue 1097 of literary magazine Akhbar al-Adab, and upon reading the pages included in the section Ibda (Creativity), declared that “his heartbeat fluctuated, his blood pressure dropped and he became severely ill.” Tawfik went to court and filed a case against the author of the text, Egyptian novelist and journalist Ahmed Naji, and the magazine’s editor-in-chief, Tarek al-Taher, for having published a “sexual article” that harmed not only his health and morals, but also the morals of Egypt as a whole.

The text in question is a chapter from Naji’s most recent novel, Istikhdam al-Hayah (The Use of Life, 2014), as was specified by the magazine. It contains explicit sexual content – as many works of Arabic literature do (see the 1994 book Love and Sexuality in Modern Arabic Literature). On November 14, Naji and Taher will have to defend themselves and the novel in front of a criminal court. The author faces up to two years in jail or a fine up to LE10,000 (US$1250) if found guilty, as the charge falls under Law 59, Article 187, which covers defaming public morals. Taher is also accused of neglecting his responsibilities as editor-in-chief of Akhbar al-Adab, since he told the prosecution that he did not read the chapter before allowing its publication.

In a Facebook status, Naji has explained that the accusation assumes that the text published is an article, and not part of a novel, which would make it a work of literature. It fails to understand the difference between journalism (supposedly based on true events) and fiction (based on imagination). It thus attributes the harmful thoughts and actions of the novel’s protagonist, Bassem Bahgat, to the author himself.

The chapter is actually narrated in first person. It recounts a normal day in the life of the 23-year-old Bassem spent in the alienating city of Cairo, a city that never sleeps, but rather “branches out” and “erupts.” Bassem finds consolation among his friends, with whom he spends the night smoking hashish, drinking alcohol, listening to music and talking about sexual fetishes. This group appears to him as the only gift he has received from the capital. Bassem spends the day after in the greener and calmer neighborhood of Zamalek with his beloved Lady Spoon, as he likes to call her because of the earrings she wears. She is described as an Egyptian Christian, educated abroad and nine years older than himself, who has decided to live the rest of her life in Egypt but has lost faith in men her age. The island of Zamalek and the comfort of her house are like a shelter inside the unstable city. The chapter culminates with a graphic and poetic description of their sexual intercourse. It ends with Bassem surrounded again by his friends, staring at the sunset from the top of Moqattam hills.

Using 19th–century jargon, the prosecutor describes the chapter as “lustful written material,” and accuses Naji of using his mind and pen for “malicious” purposes in “violation of the sanctity of public morals.” The accusation seems to disregard the fact that the novel had already received a pass from Egyptian censors, when it was imported to Egypt after being printed in Lebanon by Dar al-Tanweer.

Naji’s novel is not the first Egyptian book to be taken to court for spreading immorality. In 2008, Magdy al-Shafie experienced a similar accusationfollowing the publication of his graphic novel Metro. The author and his publishers were fined LE5,000, and Metro was confiscated and barred from publication until two years ago.

But the news of Naji’s trial immediately reminded me of an account of the trial of the Lebanese author Layla Baalbaki in 1964, which is included in the 1977 book Middle Eastern Women Speak. Like Naji, Baalbaki had been accused of having published explicit sexual content in her book Safīnat hanān ilā al-qamar (A Spaceship of Tenderness to the Moon, 1964). The questioning concerned two sentences: “He lay on his back, his hand went deep under the sheet, pulling my hand and putting it on his chest, and then his hand travelled over my stomach,” and, “He licked my ears, then my lips, and he roamed over me. He lay on the top of me and whispered that he was in ecstasy and that I was fresh, soft dangerous, and that he missed me a lot.”

Just like in Naji’s case, Baalbaki’s novel had been published nine months before, and after she obtained legal permission to print and publish it. Following the accusation, however, the book was confiscated (Naji’s novel is still available).

After more than 50 years, the account of Baalbaki’s trial, written in arid juridical jargon, can still highlight some important issues concerning the work of literature, the meaning of fiction and censorship. It raises some points that should be mentioned in defence of Naji as an author, and in defence of literature and creativity in general.

Baalbaki’s defense lawyer, only referred to as “Salim,” obtained a support letter from a committee of well-known Lebanese intellectuals, who were asked to read the novel and the rest of Baalbaki’s works before the trial. Salim argued that such a committee would be able to explain better than him “that the work under discussion is a work of literature; that its goal is to elevate literature in general, and its aims are as far as possible from arousing sexual desire in the reader and thus harming public morality.” Among the points raised by the lawyer and committee during the trial, the first concerns the role of writers and the nature of literary writing:

I would like to remind the court that the defendant is a serious writer. What is a writer? A person who tries to communicate his/her thoughts and emotions to other people through the medium of words. The author, or writer, is in a sense a camera, but one which photographs life with words, creating pictures in which we may see her thoughts and feelings clearly.

In this passage, the lawyer explains that writers of literature are endowed with a special sensibility that allows them to decipher and depict the surrounding reality for their readers. Unlike the journalist, whose writing is based on factual, reliable truth, writers of literature write about an emotional, subjective truth, based on thoughts, feelings and emotions.

In the The Use of Life chapter currently under scrutiny, Naji, far from giving us detailed information about the character, focuses on Bassem’s emotions and feelings while he wanders in the city. The sexual intercourse is depicted in a realistic manner, a mode of writing dominant in most Arabic literary production since the beginning of the 20th century (see Selim S., “The Narrative Craft: Realism and Fiction in the Arabic Canon.” Journal of M.E. Literature, vol 14, issue 1-2, 2003). Naji, just like Baalbaki, gives acts and emotions specific names in order to actualize the idea he is presenting. My reading shows that the passage is not meant to arouse sexual desire, but show that sexuality is experienced as a refuge from the bustling and chaotic city, which tends to erase humanity. Sexuality is experienced also as a liberating act in a society permeated by repressive and conservative attitudes toward the body. Indeed, Bassem ruminates: “In this city the lucky ones who overcome the phase of sexual repression find themselves in a situation in which sex is only a small component of friendship. Otherwise, sex becomes an obsession.”

It seems here that Naji is hoping to not just speak in his name, or in his fictional character’s name, but to depict the condition of a large part of Egyptian youth who struggle to survive in the capital. Bassem reflects on the fact that if you look at Cairo from above, you see that “human beings appear like ants that buy, sell and pee while the wheel of production never stops.” But standing on his feet among the crowd, he feels like “a small rat entrapped in the production wheel,” unable to get out of his cage, and not even perceiving the consequences of his own movements.

This feeling of loss and alienation in the city and in society in general appears often in Naji’s literary work. It is present also in his previous novel, Rogers (Dar Malamih, 2007), which recounts the life of a young protagonist through flashback descriptions of hallucinations induced by alcohol, hashish and the lyrics of Pink Floyd’s album The Wall. The same theme can be also found in his autofictional blog Wassiʿ Khayālak-ʿIš kaʾannak talʿab (Widen Your Imagination, Live as if You’re Playing). In this blog, Naji, adopting the fictional name Iblis (Diabolos, the devil), tempts readers to enlarge their imagination and join him in a world inhabited by spaceships and whales, where he sits beside Trotsky, Jonny Cash and Egyptian belly dancer Samia Gamal. It is somehow ironic that Naji chooses this blog title, and is then brought to court because his work is read as merely reporting reality.

Baalbaki’s lawyer goes on to argue:

It is important, for the court, your honor, to look at the book in its entirety, rather than singling out two sentences in the work as representative and stating that these two sentences alone are harmful to public morality.

This echoes Saint Augustine’s claim, written over 1,600 years ago with regard to scriptures, that meanings found in one part of a text must be congruous with meaning found in other parts. In other words, interpretations have to work for the whole text (for more on the wholeness of narrative fiction, see H.P. Abbot, The Cambridge Introduction to Narrative Fiction, 2008). Likewise, René Wellek and Austin Warren, in their Theory of Literature (1949), argue that a literary work is a “highly complex organization of a stratified character with multiple meanings and relationships” that needs to be analyzed in its entirety.

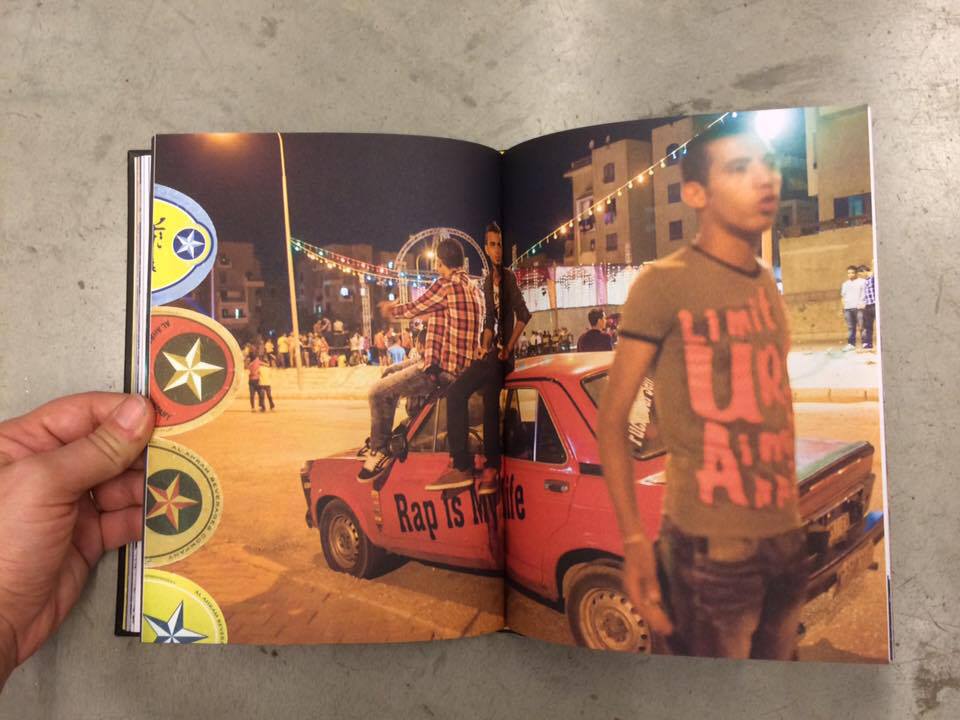

By reading the novel as a whole, one understands that it is not only about sex and drug use. The Use of Life is a hybrid work between an ordinary novel and a graphic novel, as it includes prose by Naji and drawings by Egyptian cartoonist Ayman Zorkany (some of them can be seen here). The story rotates around two main characters: Bassem and Cairo. Bassem is accompanied by his group of friends, the secret “Society of Urbanists,” who aim to radically transform the capital. Among its enemies, we find Egyptian postmodern writer Ihab Hassan and the magician Paprika, which again shows that the novel plays with surrealism and pop culture (a detailed analysis of the novel is provided by Elisabetta Rossi, translator of the novel into Italian, here).

Baalbaki’s lawyer concluded his defense by arguing that:

The concept of public morality must also be discussed, as the Lebanese legislation does not give a detailed definition of public morality, rather it is subject to change and development according to the time. They are subject to change and development also according to the writer’s time.

In the course of the past year, the Egyptian government has subjected gay men, Shias and certain belly dancers to detention and prosecution in the name of defending ‘”public morality.” In a discussion held by the Egyptian Initiative for Personal Rights in August 2015, researcher Amr Ezzat pointed out that in the debates following such citizens’ arrest and prosecution, the expression “public morality” is recurrent, but used in a very vague manner. Naji’s case, once again, brings attention to the ambiguous meaning of this phrase, at a time when sex scenes and pornography abound on the internet and television but are — sometimes — not admitted in a novel. Arguably, an accusation referring to public morality must define what is meant by “morality” in a time when leaders transgress basic human rights and persecute journalists, artists, political activists and in general the young generation that led the January 2011 uprising.

Baalbaki was finally declared innocent and the confiscated books were returned to their owners. Following the tortuous legal process, however, she almost disappeared from the literary scene and decided to privilege journalism instead.

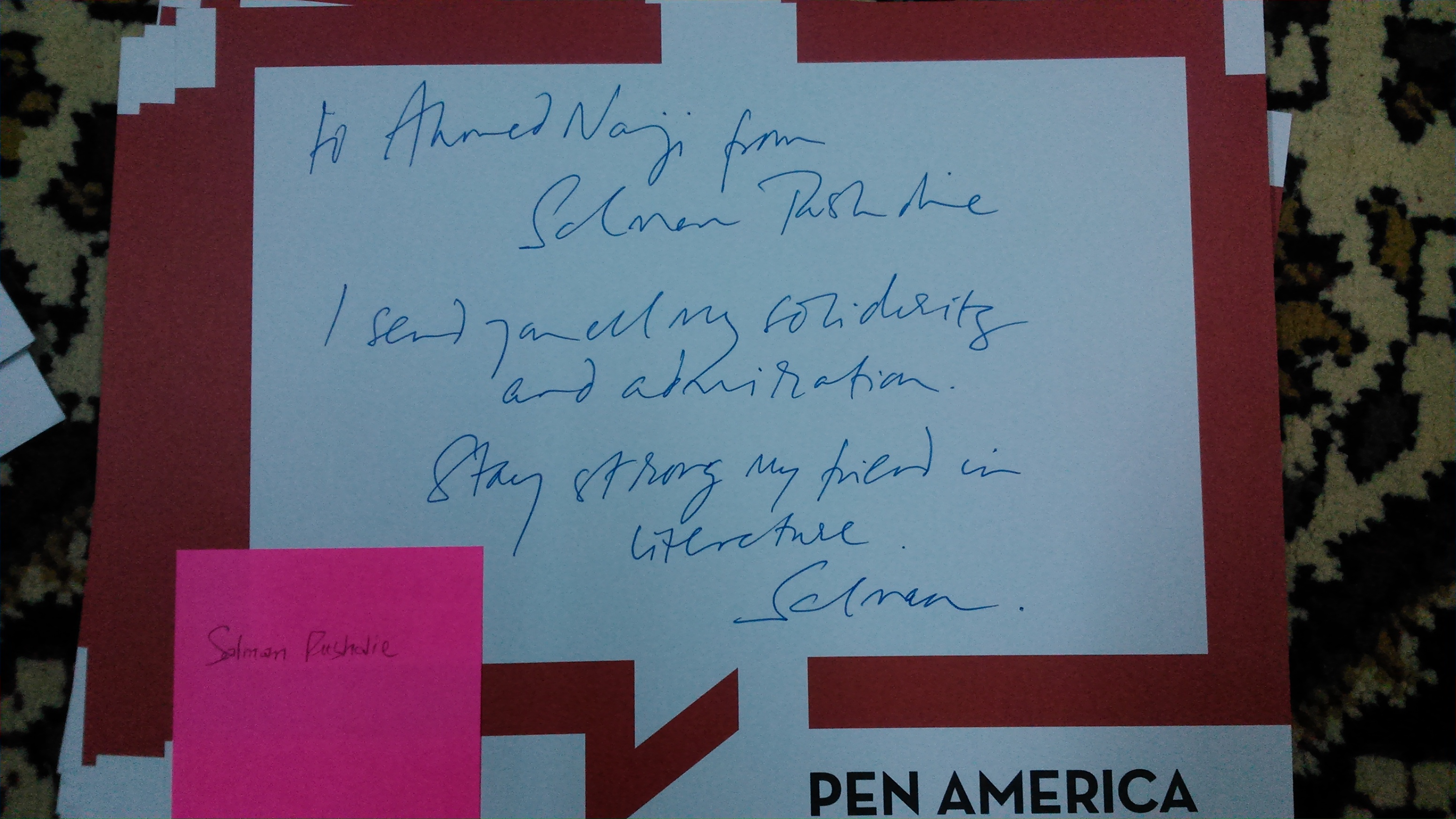

Naji will have to wait until November 14 to see how his trial will evolve. In the meantime, authors from many countries are showing their support in form of Facebook status, blog posts, articles and joining the Twitter campaign in support of the novelist using the hashtag لماذا يذهب الكلام للمحكمة# (Why do words go on trial?) in support of Ahmed Naji.

Translations of The Use of Life by Teresa Pepe.

st, you say. Tens of thousands of his fellow citizens rot in jail, where they are being abused in all sorts of ways, without any due process or a parody of it — some for

st, you say. Tens of thousands of his fellow citizens rot in jail, where they are being abused in all sorts of ways, without any due process or a parody of it — some for